Malware Samples - PMA Chapter 3

17 Dec 2025

The second chapter of Practical Malware Analysis covers virtual machine setup in preparation for this chapter and had no labs. The third chapter covers the basics of dynamic analysis and how to inspect processes, registry entries, and network traffic associated with a sample. Before running any malware for dynamic analysis, I will take a snapshot of the VM state. Even if everything appears normal when analysis is complete, I will restore to that state because there is always the chance that something was missed.

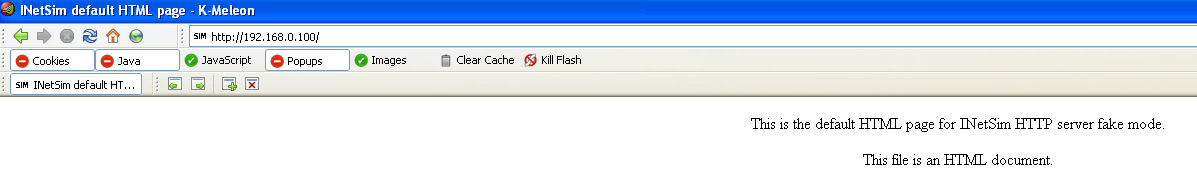

This chapter required a lot of additional setup. First, I had to set up INetSim on my Ubuntu VM to simulate services on common ports, then set up this VM and the Windows XP VM to share a virtualized internal network and assign static IP addresses. Then I set up ApateDNS to re-direct all requests to the Ubuntu VM. Now INetSim will spoof a variety of network services (pop3, http/https, dns, ftp, etc.):

Samples:

Malware Sample 1

This is my first dynamic analysis sample and the process was much more in-depth than the dynamic analysis I performed in my malware class.

Questions:

- What are this malware's imports and strings?

- What are the malware's host-based indicators?

- Are there any useful network-based signatures for this malware?

What are this malware's imports and strings?

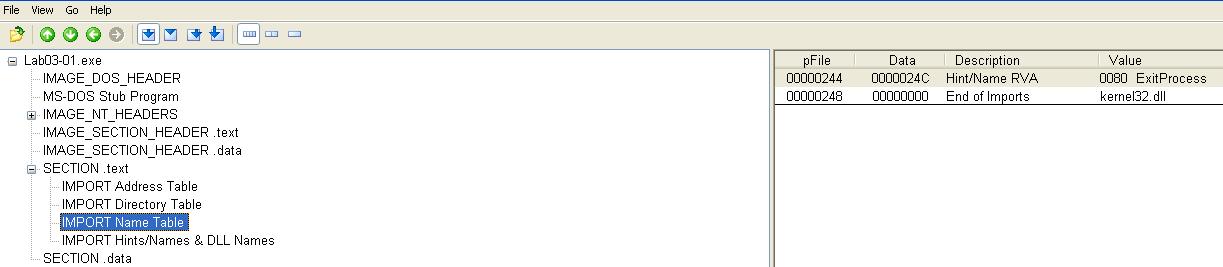

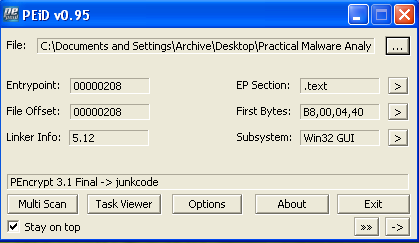

Although the section sizes don't indicate packing, the lack of imports shown in PEView does:

A quick check in PEiD confirms this:

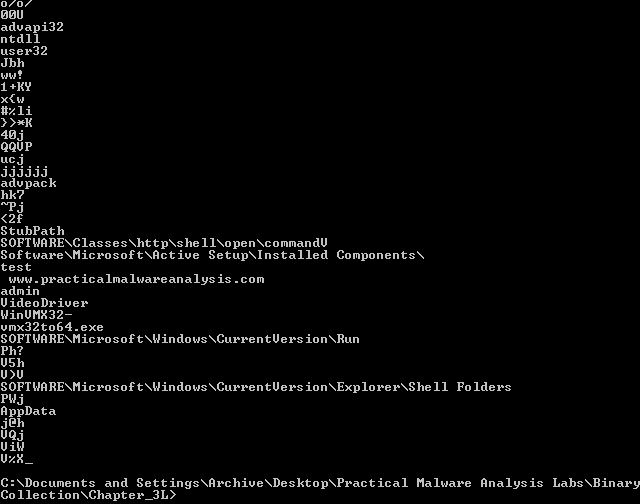

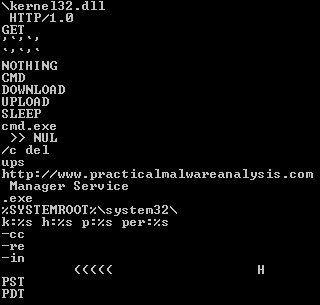

I couldn't find any software to unpack this and this is supposed to be a dynamic analysis lab anyway, so I'll continue to check strings using Microsoft's strings.exe:

Along with a URL and some registry paths, it also looks like some additional imports are visible here.

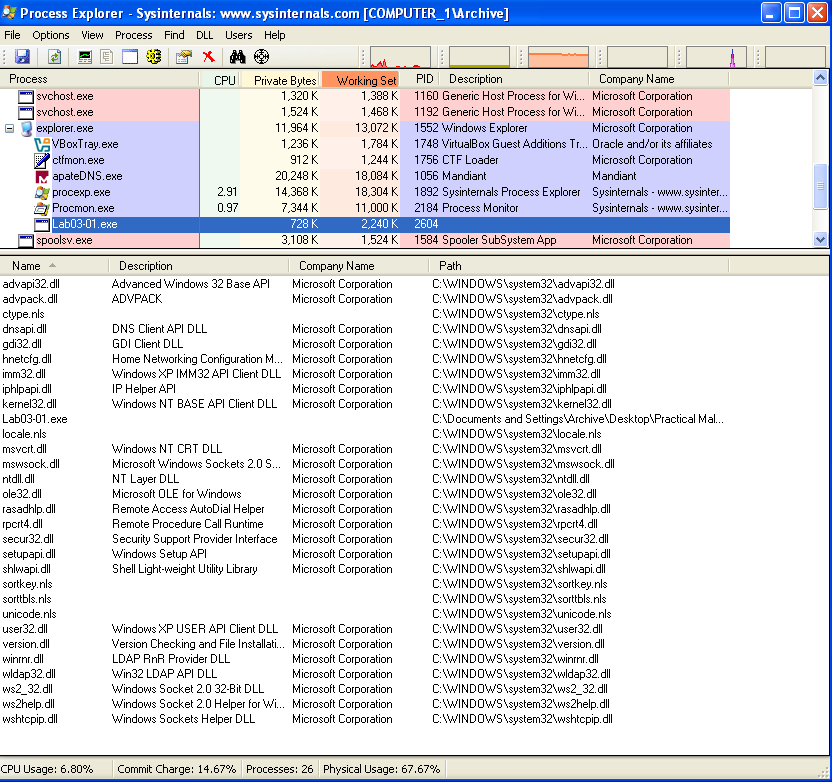

This was as far as I could get with static analysis, so I set up Process Explorer, procmon, ApateDNS, Wireshark, INetSim, and fired off the sample. Process Explorer showed a lot more imports than were visible with static analysis:

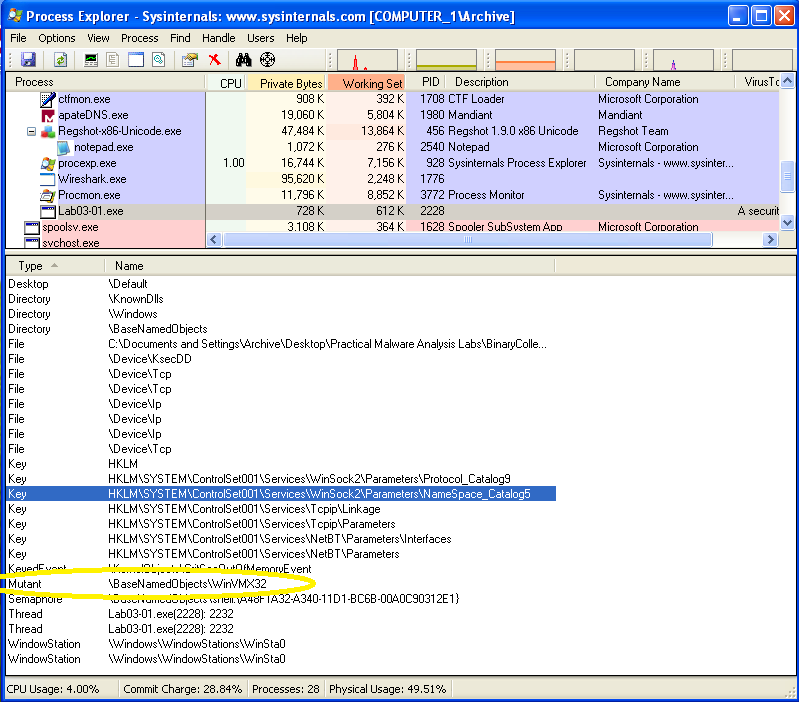

Also, looking at the handles in Process Explorer reveals a mutex that was created:

What are the malware's host-based indicators?

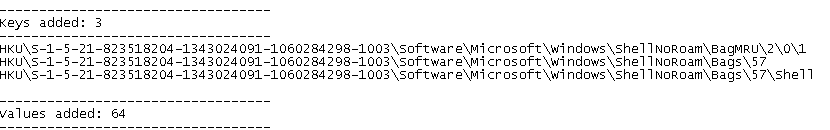

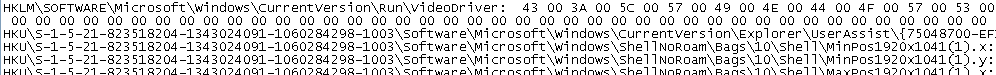

Before running the sample, I took a snapshot of the registry with Regshot and another afterwards. Comparing the two shows a lot of activity in the registry:

This line was particularly interesting because it adds something to run on startup:

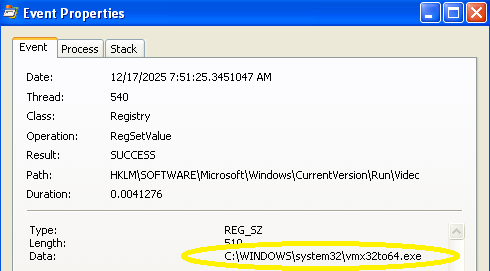

The hex string could be decoded, but it was easier to just view the properties of this operation in procmon:

Here's that mutex from Process Explorer!

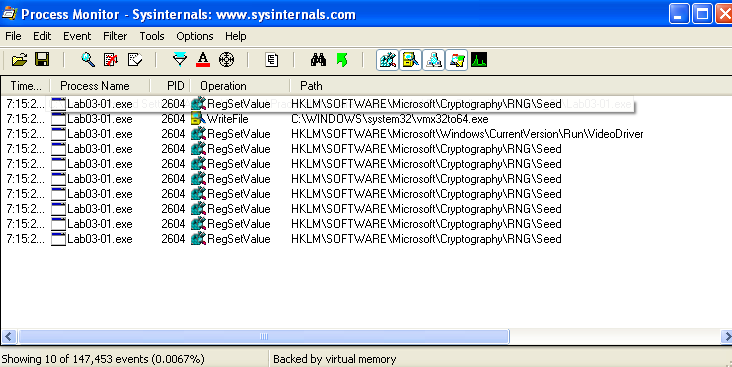

Filtering on the RegSetValue and WriteFile operations in procmon shows these results:

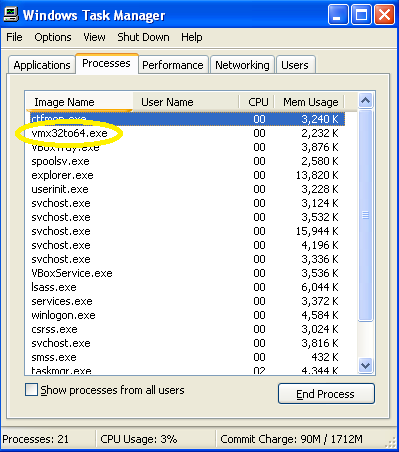

I was curious if it started this process at runtime, so I restarted the VM to check, and there it is!

Host-based indicators for this sample would be any reference to vmx32to64.exe.

Are there any useful network-based signatures for this malware?

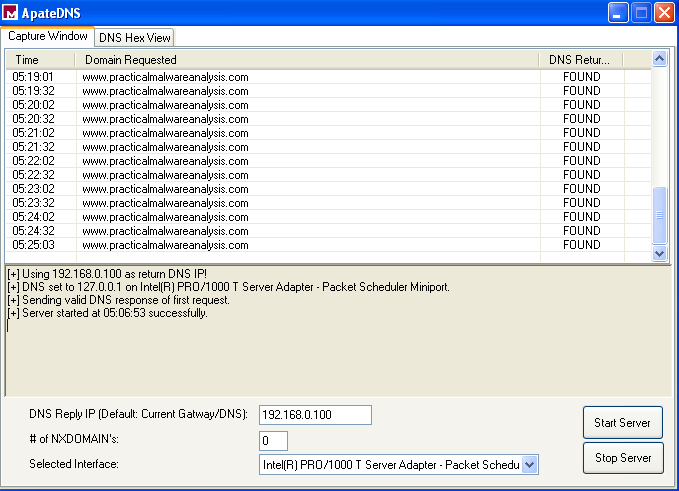

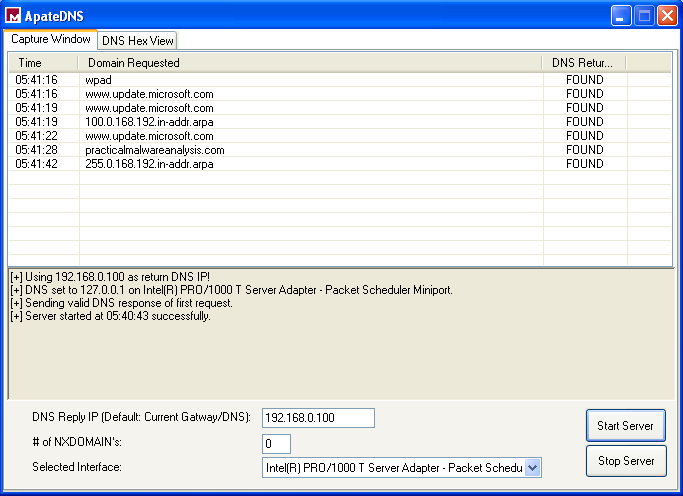

I had three network utilities (ApateDNS, INetSim, Wireshark) set up to analyze this sample. All showed the same results, but ApateDNS was the easiest to monitor:

Every 30 seconds this sample sent requests to www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com, which would be the only network-based indicator.

Every 30 seconds this sample sent requests to www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com, which would be the only network-based indicator.

Wireshark showed that these were SSL requests on port 443.

Malware Sample 2

This sample is only a DLL, but when installed it creates a malicious service.

Questions:

- How can you get this malware to install itself?

- How would you get this malware to run after installation?

- How can you find the process under which this malware is running?

- Which filters could you set in order to use procmon to glean information?

- What are the malware's host-based indicators?

- Are there any useful network-based signatures for this malware?

How can you get this malware to install itself?

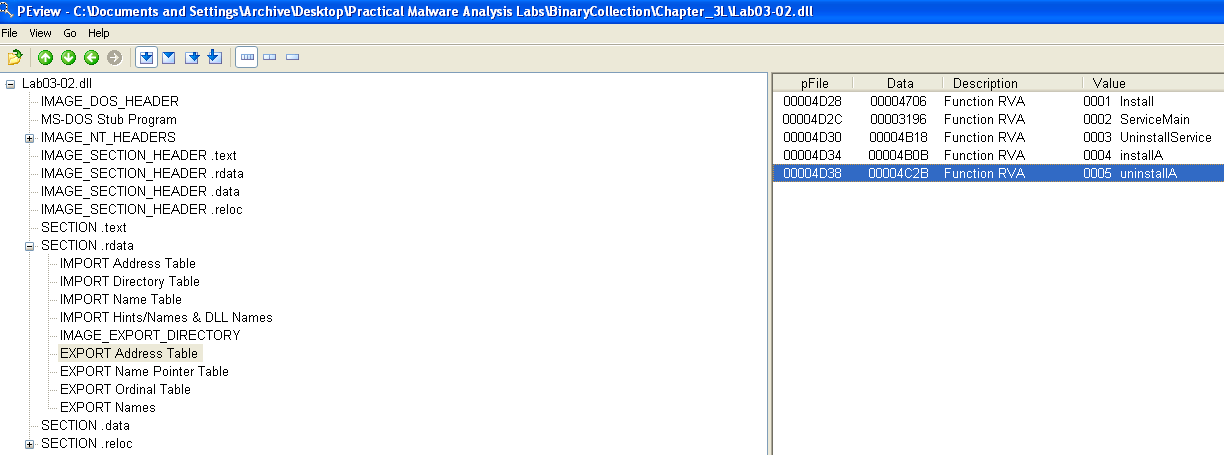

Looking at the exports for this DLL in PEView, there are two install functions defined:

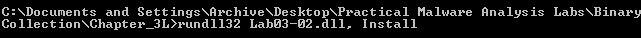

After setting up all dynamic analysis tools, I will try the first Install function using rundll32.exe:

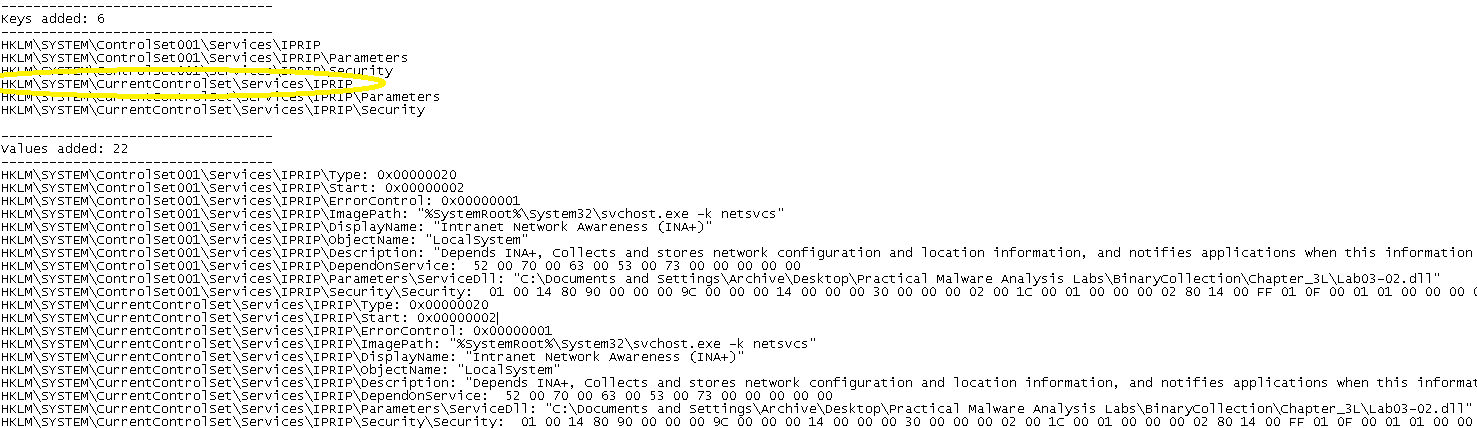

A comparison of before and after registry snapshots with RegShot revealed nothing interesting, so I tried again with installA. Now there's something interesting; a newly-installed service named IPRIP:

How would you get this malware to run after installation?

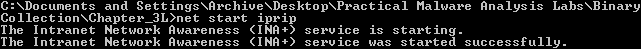

To run this malware, the new service will have to be started:

How can you find the process under which this malware is running?

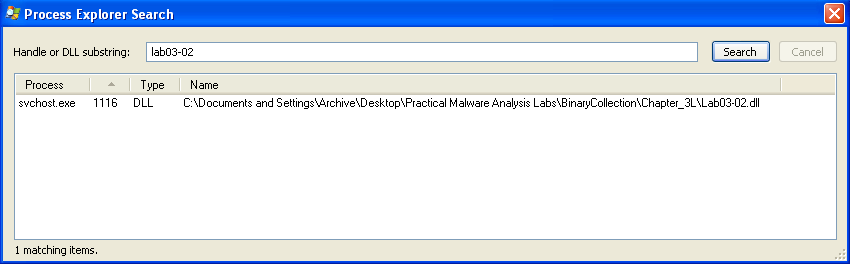

Now that the new service is running, the process using it can be identified by searching for the malicious DLL in Process Explorer:

Which filters could you set in order to use procmon to glean information?

There are many instances of svchost.exe running, so the PID of 1116 will need to be used as a filter for procmon. This was a busy process and after a lot of scrolling and applying different operation filters, its main local functionality seemed to be reading system/network settings and writing to log files.

What are the malware's host-based indicators?

The main host-based indicators for this sample would be registry entries for the malicious DLL and the IPRIP service it installs.

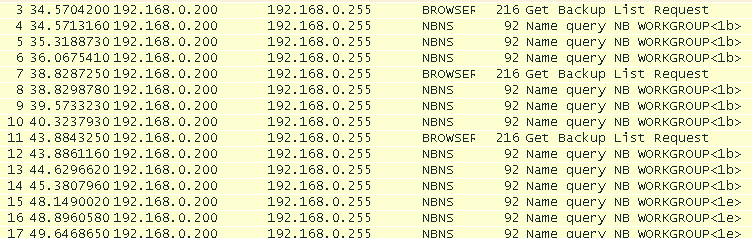

Are there any useful network-based signatures for this malware?

Starting the IPRIP service revealed several network-based indicators. First, a backup list request is made on the local network to identify targets:

Next, a request was made to practicalmalwareanalysis.com:

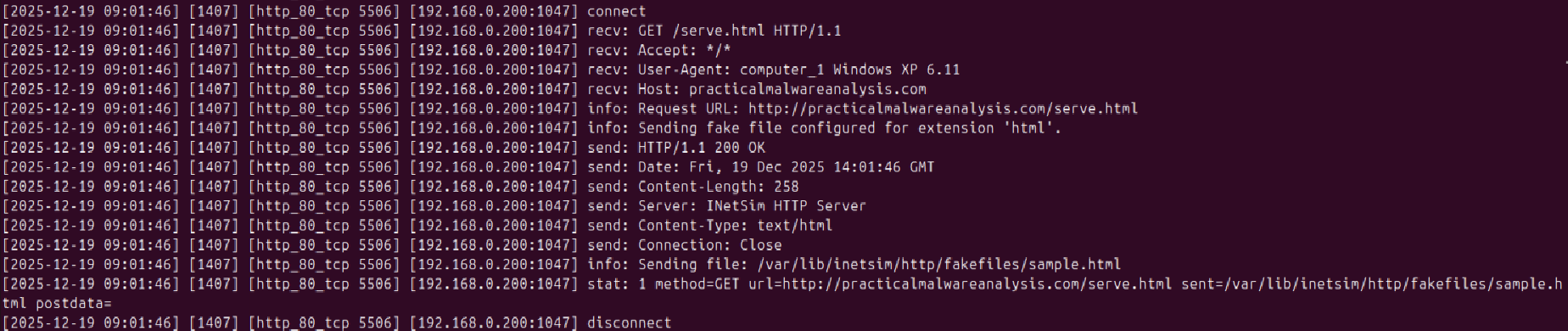

Checking the log details from INetSim on the Ubuntu VM shows a GET request for the file serve.html and INetSim sent back a fake .html file (what a cool tool!):

The main network-based indicator for this sample would be URL the GET request was sent to and in the event that this malware were real, any files requested.

Malware Sample 3

The third sample only requires host-based analysis and does some interesting tricks with process manipulation.

Questions:

- What do you notice when monitoring this malware with Process Explorer?

- Can you identify any live memory modifications?

- What are the malware's host-based indicators?

- What is the purpose of this program?

What do you notice when monitoring this malware with Process Explorer?

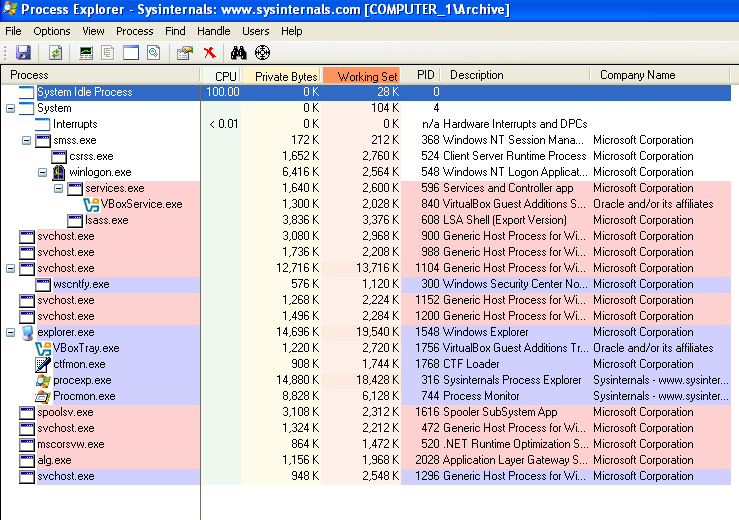

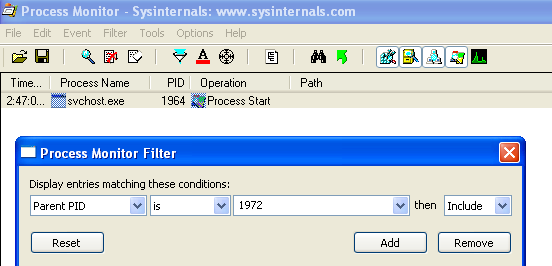

Without this question, I probably would have had to run this a few times to notice, but if you watch Process Explorer when running this sample, the Lab03-03.exe process begins, spawns a svchost.exe process, then the Lab03-03.exe process terminates. This happens too quickly to capture a screenshot, but here are the running processes afterwards:

Can you identify any live memory modifications?

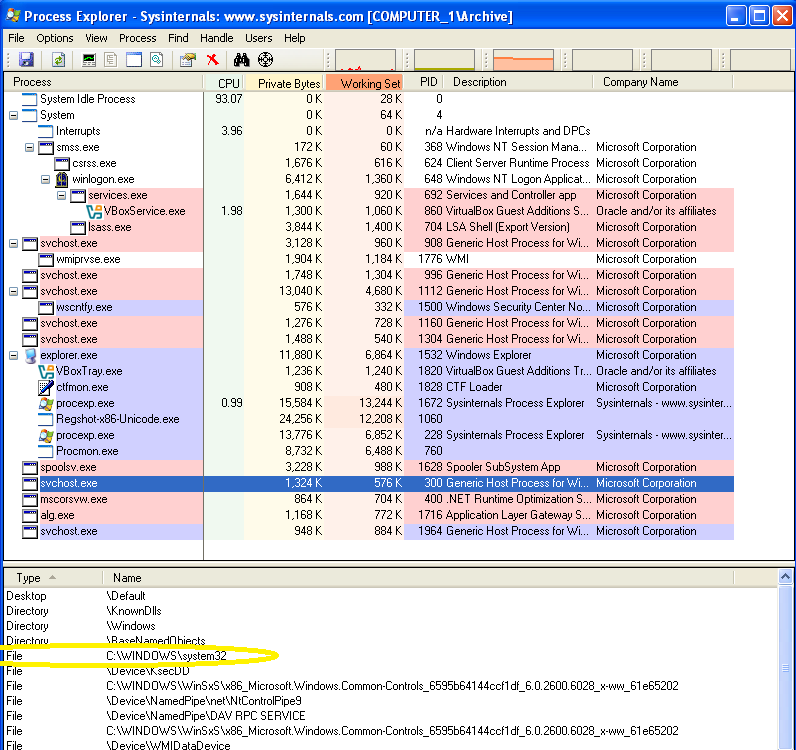

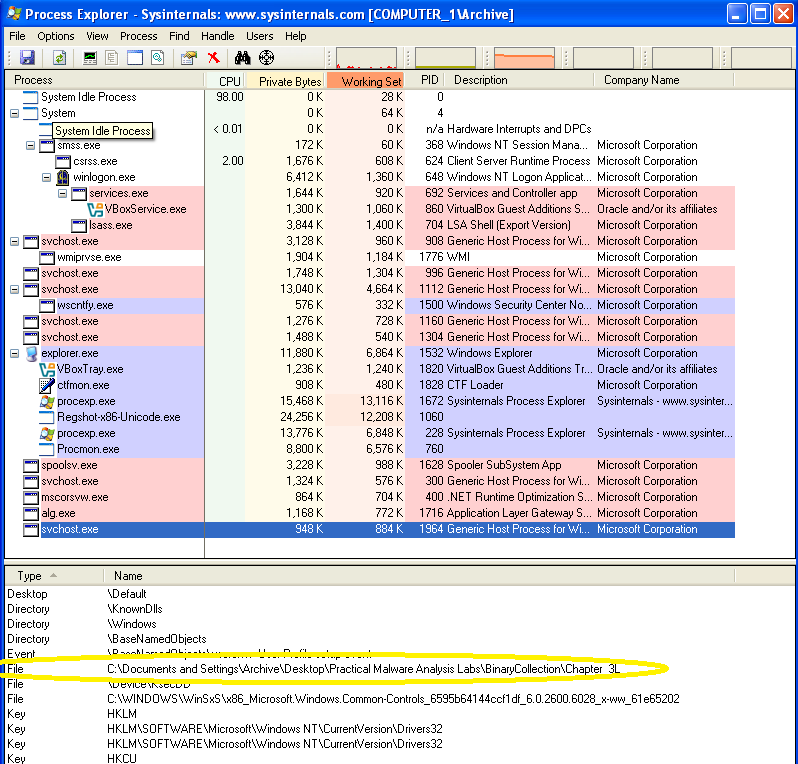

In a normal svchost.exe process, the file that process is spawned from is located in C:\Windows\system32:

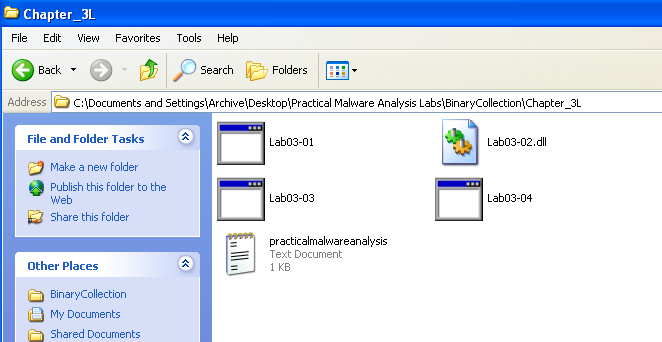

For the malicious process, the file is located in the malware sample directory:

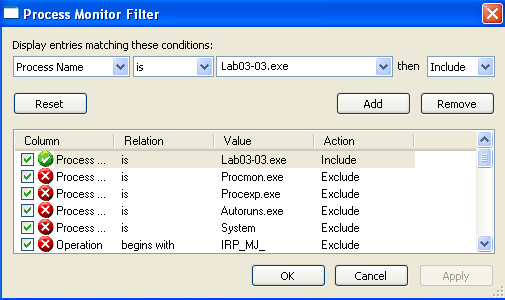

Since it was observed that a process was created, another way to locate this process would be setting filters in procmon. This first filter gave me the PID for the original Lab03-03.exe process:

Using that PID allows a search for its child processes:

What are the malware's host-based indicators?

The first host-based indicator would be the creation of a svchost.exe process based on a different file from another directory. Looking at the procmon results from that process reveals another indicator:

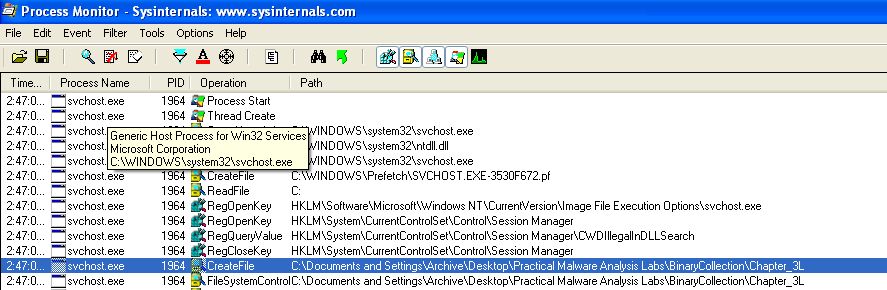

The second indicator would be the creation of the practicalmalwareanalysis.log file:

What is the purpose of this program?

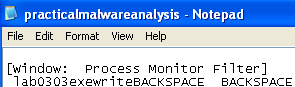

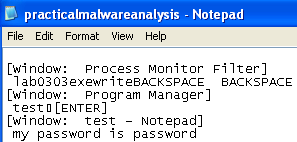

Opening practicalmalwareanalysis.log gives an interesting clue:

This looks like what I typed in the procmon filter earlier.

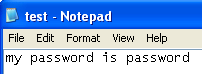

I created a test text file and did some more typing:

Sure enough, it looks like this is a keylogger!

Malware Sample 4

The fourth sample is an introduction to malware that employ anti-analysis techniques. This sample was tricky to analyze and will be re-visited in Chapter 9.

Questions:

- What happens when you run this file?

- What is causing the roadblock in dynamic analysis?

- Are there other ways to run this program?

What happens when you run this file?

Well, let's just double-click Lab03-04.exe and find out:

Wasn't expecting that!

What is causing the roadblock in dynamic analysis?

It appears that this sample is possibly employing some type of anti-analysis technique and deletes itself. After trying to repeatedly run the sample adding one analysis tool at a time, I discovered that it only deletes itself when the network is monitored. Even trying to redirect requests to the Ubuntu VM by editing the hosts file still results in self-deletion.

Are there other ways to run this program?

Looking at the strings results, it does appear that there are a few flags that can be used when running this sample:

Unfortunately, all of these still result in self-deletion. After exhausting all of the techniques learned so far, I resorted to the solutions appendix and was relieved to find that this was the expected result. More advanced techniques are required and this material will be covered in Chapter 9. I look forward to learning what the solution is!

Conclusion

This chapter was an excellent introduction to dynamic analysis and gave me some experience with process, service, and DLL analysis (even a small taste of anti-analysis techniques). Setting up a second Ubuntu VM with a virtual network to mimic a C2 server was also a valuable learning experience. This built a lot on the dynamic analysis techniques I learned in CS 6747 and I look forward to learning even more advanced techniques in future chapters!